Why do you write Crime Fiction?

Conflict is king

Friday afternoons drag. If you work in an office, it can feel like the devil has planted one of his hooves down on the minute hand of the clock, slowing down time to where it starts to hurt. The happiness you felt earlier in the week has gone; the bright colours of life have faded, and all that remains is a seemingly endless, black and white, nothingness. Punctuated by the random antics of work colleagues, who are even more insane than you are.

And then Friend K asks: Why do you write crime fiction? This is not a question I've been asked often. The short answer is: That's the way I am.

First of all, I actually think of myself as a mystery writer, not specifically a writer of crime fiction. I like mysteries, and at the heart of every story I've written you'll find one. It's a fundamental "human thing" to look for meaning in things we don't understand, to want to bring order to the chaos of life. Who, as a kid, hasn't looked to the stars at night and wondered what's out there? My foremost pleasure in writing a story is engaging the reader in some kind of problem or enigma that needs/demands to be unravelled and solved. Seeking resolution makes readers keep turning the pages.

I grew up watching dozens of TV shows and movies about detectives and police officers. The mystery of who did it, how they did it, or why they did it, is central to any story in this arena; it's their raison d'être. I also grew up loving science fiction, because in sci-fi, the mystery can be as big as the universe. My favourite TV show is The Twilight Zone.

The thing I like about the Twilight Zone is that no matter how "out there" the stories were, they were mostly stories about real people. Rod Serling (the show's creator and principal writer) even said so. Setting stories in the "twilight zone" enabled him to explore almost anything about the human condition, that placed in a "realistic" or contemporary setting, he would never have gotten past the network censors or advertisers.

I don't write a lot of science fiction because I mostly prefer realistic settings and situations. I'm more interested in the girl hiding her dead boyfriend's body after she strangles him, rather than the girl who has three eyes and a luminous tail.

So, mysteries and stories about real people.

Picture a classroom in a suburban high school. The building is barely three years old, and everything still has the feeling of the new and the modern about it: spacious, large windows, well lit. Teacher M is standing at the front of the room. She's middle-aged, has dark hair, glasses, and a curious sense of humour. She's written "What makes a story work?" on the blackboard. It's English class, the last class before lunchtime on a Friday. The class is filled with a bunch of tired students daydreaming about the weekend, their sandwiches, or the cute boy/girl seated in front of them.

This was a question that caught my attention and woke me up. No one in the room had an answer, not even Student D, the cute girl who sat in front of me in the front row, who usually had an answer for everything. In fact, she turned around to see if anyone else was putting up his/her hand. We traded vacant shrugs.

Teacher M wrote the answer on the blackboard. "Conflict."

She explained: Stories work when people are in conflict with someone, something, or themselves. She cited three examples from our reading that year:

Romeo and Juliet's happiness in their love is prevented by the conflict between their two families.

The conflict in The Importance of Being Earnest is the misunderstanding (lies and confusions) that exist between most of the characters.

In To Kill a Mockingbird, Atticus' decision to defend a man he believes to be innocent in a rape trial threatens his family's safety.

Teacher M summed it up: Conflict is a problem to be resolved. The conflict and its resolution ARE the story.

A story about a man who wakes up on a nice sunny day, goes out and buys groceries, and then comes home again, will not be very interesting or memorable. Without conflict, there's nothing to be engaged with.

So, mysteries, realistic people in realistic situations, and conflict – the evolution of my writing gained mass around the nucleus of these three core components.

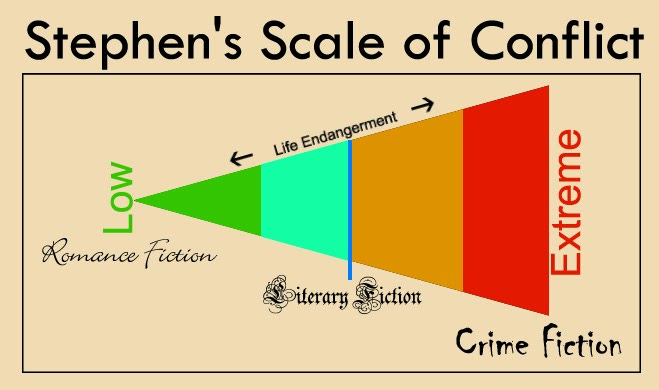

There are, of course, degrees of conflict. A misunderstanding where a guy asks a girl on a casual date and she misinterprets his intentions is at one end of the conflict scale. A man murdering another man because he stole his girlfriend is at the other. The scale itself is one of life endangerment – the higher the risk, the more extreme the conflict.

As a writer, I lurk at the extreme end of the scale. Heightened conflict engages the reader (and me). I simply find it more interesting to write about people in deeply dramatic situations – more often than not, that involves some kind of crime. Had I not been so inclined, I might have become a romance writer, or a writer of literary fiction.

I don't know if my scale of conflict (illustration above) actually holds any water, I only just made it up (on the day before you read this) so I haven't had time to really think about it. Feel free to shoot it full of holes.

Anyway, that's why I write crime fiction.

First published: Sleuthsayers.org (October 28, 2014)

Text & Photos ©2014 Stephen Ross